The fun and science of blacklight

by Paul Huber

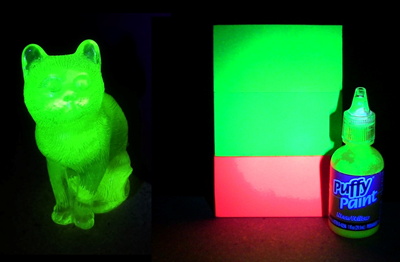

Blacklight reactive materials. Uranium glass cat, fluorescent dye posterboard, and phosphorescent paint

illuminated by 380 nanometer LEDs.

My love of blacklights probably began before my teens, with the Spencer Gifts

store in the new shopping mall they built nearby. I would go there periodically with my friends for

something to do, mostly just walk around, but we always went in that store to see what they had. The back

section was partitioned with a curtain of hanging beads and that’s where all the cool lighting was. I

loved that atmosphere and it always had a positive effect on my mood for some reason. Four foot purple

lamps mounted on the ceiling illuminated our clothes, blacklight posters, and glow-in-the-dark novelties,

and it made me want to have my bedroom like that.

The first blacklight I got was an ordering mistake – a 24” fluorescent tube with the catalog number

F20T12BL. The ‘BL’ suffix designated blacklight, meaning the phosphor of the lamp was optimized for

ultraviolet output, but it didn’t have the dark filtering glass of a ‘BLB’ (black light blue) lamp. That

meant that it generated the blacklight glowing effects but they were largely spoiled by visible light that

was not prevented by the filtering glass. Well, I learned something and later bought a proper F20T12BLB

and enjoyed my new environment.

Blacklight is special for two main reasons: The ultraviolet light is high enough in energy to excite

electrons in the reactive material, making that material glow, and it minimizes visible light that would

wash out or reduce the visibility of that glow. Sunlight is high in UV but the visible light is so bright

that we can’t appreciate the effects of it.

Let’s look at reason #1 - light energy and wavelength. Light, as we generally think of it, is part of

the electromagnetic spectrum. In fact, the only difference between light, radio waves, or x-rays is the

wavelength of their electromagnetic energy. Visible light, the narrow portion that the cells in our retina

respond to, is typically defined as 400 to 700 nanometers in wavelength. This varies slightly according to

the individual’s sensitivity, but the 400 end is violet in color and 700 is the deepest red. Below 400

nanometers is ultraviolet, x-rays, and gamma rays. Above 700 nanometers is infrared, microwaves, and radio

waves. Wavelength has a corresponding frequency and photon energy, and the shorter the wavelength the

higher the frequency and photon energy.

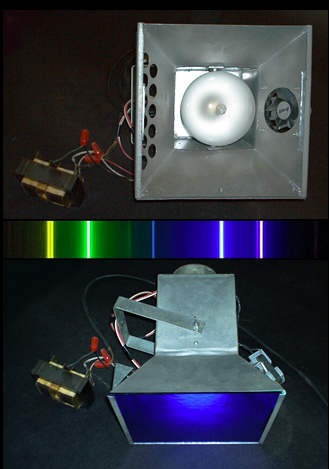

175 watt mercury vapor blacklight flood I made for a Halloween party. Cobalt-blue glass was used for the

filter lens. It blocked the yellow and green emission lines but transmitted the blue, violet, and UV.

Normally the blue light would be unwanted but it gave a nice eerie glow to the party scene. The fan is for

cooling the filter glass which gets hot from absorption.

Blacklight is part of the ultraviolet spectrum, which is sub-divided into three categories: UV-A

(400-315nm), UV-B (315-280nm), and UV-C (280-100nm). Although all three can generate visual effects, only

UV-A is considered safe for human exposure, and ~365 nanometers is considered the optimum blacklight for

both effects and safety. This wavelength has a corresponding photon energy of ~3.4eV (electron-volts). By

comparison, 470nm (blue) is ~2.6eV and 660nm (red) is ~1.9eV. The higher photon energy of blacklight is

important in reaching the threshold necessary to excite electrons in blacklight-reactive materials

(fluorescent and phosphorescent). We’ll discuss these, and why they glow, further down.

To produce the best blacklight effects you want to give good consideration to the lamp type so that

it maximizes high-energy ultraviolet output and minimizes visible light that would spoil those effects.

Incandescent bulbs are still sold and are the cheapest, but they are also the least efficient and

effective – so much so that they aren’t worth buying unless you just want the look of a purple bulb. The

reason is how they produce their light. A tungsten wire filament is electrically heated to the point of

giving off light through thermal radiation. Typically operating around 2,800 Kelvin, the filament

emits a spectral curve roughly equal to a blackbody radiation curve at that temperature. As you can see

in the graph most of the energy is in the infrared, less than 10% is visible light, and almost none of

it is useful UV.

Prior to around 2015 fluorescent lamps were the best. Mercury vapor and metal halide lamps

(using custom arc tube ingredients) were also popular for entertainment and commercial displays where

high output was needed, such as Disney’s Haunted Mansion or theater productions. Fluorescent lamps are

efficient because they use phosphors that are optimized for output in the blacklight spectrum and are far

superior to incandescent. They do require a fixture with a ballast device but it’s typically the same as

types used for conventional lighting, so mass production keeps these fixtures within a reasonable cost.

The exception is compact fluorescent blacklights which have an electronic ballast integrated into the

base of the lamp. These are typically inexpensive and a great choice.

Clear mercury vapor lamps have a strong natural emission line at 365.4 nanometers and they have been

used as a source for many decades because of that. They are not as efficient as fluorescent but higher

wattages (400 and 1,000) and compact arc length made them useful in floodlights and spotlights for larger

applications (mentioned previously). Metal halide lamps are a sort of hybrid mercury lamp with added

metallic ingredients in the arc tube to improve color output and efficiency. Wildfire Lighting provides a

specialty lamp of this type that’s optimized for blacklight applications called IronArc®. At the time of

this writing they are still selling the replacement lamps but the fixtures have been dropped from their

website, so I assume that these, as well as mercury vapor lamps, are being phased out for blacklight

production.

LED has become the present and future of blacklight technology. Fluorescent is still popular, and will

continue to be for some time, but LED lamps are now on par because of advancements in the diode chip

material that allow for the production of shorter wavelengths. Japanese professors Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi

Amano and Shuji Nakamura won the 2014 physics Nobel Prize for inventing the blue LED in the 1990s. The

discovery in material moved LEDs beyond their previous green color limit and made things like LED bulbs

and Blu-ray disc possible. Since then, the spectral output of LEDs has advanced all the way to 265nm

(UV-C), which can be used for germicidal or resin curing applications. The top image of this article was

made using 380nm LEDs that I purchased for less than $1 each; and 365nm LEDs (the ideal) are now mass

produced for blacklights of various forms. One of those forms is a fluorescent-style tube that can be

used as new or as a retrofit in existing fluorescent fixtures that use an electronic ballast.

All of the lamp types above, from incandescent to LED, produce visible ‘waste’ light and work best

with a filter that blocks that visible light but allows the UV to pass through. It can be integral to the

lamp envelope or separate as part of the fixture. The first such filtering glass was called Wood's glass,

invented in 1903 by physicist Robert Wood. This type of bandpass, or longwave, filtering glass is still

often called Wood’s glass but is usually a more modern formulation. The filtering glass is what gives

blacklight lamps their dark purple appearance.

But all of this is about the fun, glowing effects. We need to talk about the stuff that glows and

why!

Materials that glow under blacklight are called blacklight-reactive and divide into two categories:

fluorescent and phosphorescent. The simple difference is that fluorescent material only glows while the

blacklight is shining on it, but phosphorescent material continues to glow afterward and is called

glow-in-the-dark. The explanation for this difference is a quantum mechanical phenomenon called electron

spin.

Both materials absorb UV photons from the blacklight source. The term ‘photon’ was created in 1926

and is best defined as the smallest unit of radiant energy. When the photons are absorbed they excite

electrons in the reactive material molecules to a higher ‘excited’ state which cannot be sustained and is

temporary. Eventually they fall back to their normal ‘ground’ state, emitting photons as they lose that

energy. The reactive material becomes an actual light emitter as that happens, showing off its own color

according to the wavelength of the newly emitting photons. The difference in wavelength between the

absorbed photons and emitted photons is called the ‘Stokes shift’ and is due to other energy losses during

the process. For fluorescent materials, this ‘ground state to excited and back again’ process occurs

within a tiny fraction of a second and is essentially instantaneous relative to our perception. With

phosphorescent material, however, something additional happens in between. The excited electrons also

change their ‘spin’ state, making this glow-in-the-dark material unique. Once changed, this spin state

must reverse back before the electrons can return to their ground state and that spin reversal is

physically “forbidden” except under conditions that take time to randomly align. This process can take

minutes to hours, delaying the emission of photons, and making the material glow long after the exciting

light source is turned off. These processes are shown in a diagram called the Jablonski Diagram, named

after a Polish physicist Aleksander Jablonski. The video explanation included here I thought was quite

good and worth a watch.

Well, that might have gotten a bit long but there’s really a lot to it and much more to explore for

someone interested. The physics are as fascinating as the effects are fun and I hope you share some of my

enthusiasm for it. Now it’s time for that blacklight party or Halloween display and to

have some fun!

Further:

Electromagnetic spectrum

Wood's glass

Stokes shift

Electron spin