1999 was a very exciting

and anxious time! I got caught up in it myself and even bought one of those Millennium

countdown clocks (it still works and sits on my desk as I’m writing this). The coming

New Year’s celebration had been anticipated for over a decade, but the potential Y2K

crisis gave it a dimension worthy of a blockbuster Hollywood sci-fi film.

Articles on IT sites and in magazines about the problem gradually appeared, then

increased, during the 90s. By 1998 they were beginning to take on a hyperbolic

tone and it was hard to determine what might be the reality from all the predictions

that were being made.

I vividly remember the moment when I knew that the press was indulging in exaggeration.

I was sitting in the customer waiting room of a local electric utility, waiting for

some new metering equipment for a job I was doing. I was passing time reading a

prominent news magazine. The article was about the year-2000 issue and the author

was explaining that almost everything electronic had a microprocessor in it, and was

therefore vulnerable to the Y2K glitch. Listed among these things were microwave

ovens and toasters… Toasters?

"I knew someone who stopped paying all their bills because

they actually thought it was going to be

the end of the world."

Being an electrician, and someone who loved to take things apart, I knew that most

toasters – perhaps 99% - operated with a bi-metal release mechanism. This was a strip

composed of two bonded metals with dissimilar coefficients of expansion. When the

strip got hot one metal expanded more than the other, causing it to bend and release

the spring-loaded toast tray within the appliance. There was no microprocessor, no

program code, and it sure didn’t know or care what year it was. The author had clearly

gone for the “big story” effect.

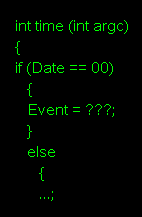

So what was the real scope of Y2K? Was it really a looming disaster or just a bunch

of made-up hype? Like most debated issues the truth was somewhere in the middle. To

test my own PC (an 80386DX running Windows 3.1 – no laughing please!) I booted into

the BIOS then set the date for 12/31/1999 and the time for 11: 55 p.m. I re-booted

the computer into Windows and opened several programs. I proceeded to use the computer

as I normally would until the time had passed well into “1/1/2000”. There were no

problems and a re-inspection of the BIOS showed the four-digit year of 2000. I came

to the conclusion that this was mostly hype.

To get a clearer picture of Y2K ten years later, I contacted Chris Kremer with

CVK Technical Consulting in Buffalo, NY. His perspective of Y2k turned out to be somewhat different

from my own, mainly since his experience was with custom-written legacy software for

larger businesses. Here is what he shared with me.

Q. Do you remember how you first became aware of the year-2000 issue?

I became aware of the Y2K issue in 1990 during a Y2K awareness conference in Reston

Virginia while working on a federal government contract. I learned that many programmers

had used 2 digits for recording year data instead of 4 and that this was going to cause many problems.

Q. Were your clients anxious about it or did you have to persuade them to

take preventative measures?

All of my clients took the issue very seriously and began to conduct audits to identify all of the

applications that were going to be affected by the issue.

All of my clients took the issue very seriously and began to conduct audits to identify all of the

applications that were going to be affected by the issue.

Q. Was there a point where you thought the media may have been exaggerating the scale of the problem?

No, because I was exposed to many diversified proprietary software applications and I understood

how they functioned. I understood programming and date mathematics. By the time the media was reporting

the issue, I knew and understood the effects of having the date rolled back 100 years and what that

could do to these systems. I knew that any applications that used date codes for calculating

were going to be a problem. I had already worked on many projects that involved conducting simple

experiments by changing the year in software applications to 2001 and beyond and noting the results.

Q. Do you think IT vendors exploited the fear to sell new equipment and software?

No, but I would say that the whole Y2K issue was the result of the human condition. Humans are flawed

and many do not think about the future. When programming complex software it was shortsighted

to use a 2-digit-year field instead of 4. If 4 digits were used in every application

that was developed, then the issues would have never existed. Some people may even say that it was

planned obsolescence; in a few cases I believe that it was. For the majority of cases it was human

error. Think of a bank -- they operate their entire production from date mathematics and many banks

employ their own in-house software development team. There is no profit in developing a banking

application that is limited to 2 digit date codes. Not all banks had the problem; the ones that were

affected had to spend a lot of money to fix the flaw.

Q. What computer systems do you know of that were actually affected?

Hardware was not the major issue; it was software that was affected. I know of hundreds of

applications that were affected including applications for payroll processing, industrial

manufacturing and production, project management, accounting, security systems, and medical systems --

the list goes on and on.

Q. Do you have any guess of how much preventative work was actually necessary?

Preventative is not the term that I would use. It does not take much work at all to be preventative,

namely, have a 4-digit year code in the software. The programmers with the flawed software should have been

preventative. The term that I would use is reactive, because companies had to spend hundreds of hours

auditing their systems to discover all of the applications that required work to correct the problem.

Once the issues were identified, they had to figure out (a) if it was worth doing minor changes or (b) if it would

be better to re-write the entire application and make other improvements along the way or (c) purchase and

implement new third party applications. It really was a big deal identifying and documenting the problems,

considering all of the options and then managing the solutions.

Q. What are the most extreme cases that you remember?

I knew someone who stopped paying all their bills because they actually thought it was going to be

the end of the world. They ended up losing their house and many of their personal possessions because

of this thinking. I also knew of some companies that were owned by multi-millionaires that were

so uninformed and cheap that they did nothing at all about the issue until their whole business was affected;

all of their employees were so stressed during January of 2000 that some actually quit.

All of these companies have since gone out of business.

Q. What do you think were important things to learn from this?

The success of any project is all about the personal philosophy of the people working on the project --

how they think as individuals, how they work as a team, what contributions they make during the project,

and how dedicated they are to achieving the end result.

Chris Kremer is an IT professional and owner of

CVK Technical Consulting